In Britain, we love a good cup of tea – and it’s not just us! Worldwide, tea is the second most popular drink after water and it’s easy to see why. A range of aromas, colours, tastes, and potential health benefits partly explain its popularity, but the main appeal is the all-important energy boosting effect of caffeine.

What is caffeine?

All tea types (black, green, white, oolong, and pu-erh) are prepared from the leaves of an evergreen plant called Camellia sinensis. The leaves produce an alkaloid called caffeine, which researchers believe acts as a natural pesticide to paralyse or even kill would-be predators. However, at an appropriate dose in humans, it acts as a stimulant. Although coffee is famous for its caffeine jolt, tea can actually contain more caffeine in its natural state. Tea usually contains around 2- 5% caffeine by weight whereas coffee contains ~3%. In practice, the average cup of tea has 20-40 mg per cup whilst coffee has around 80-135 mg, because less tea (1-3 g) is used per cup compared to coffee (5-10 g).

Is caffeine good for you?

Caffeine blocks the adenosine receptors, giving a feeling of alertness which people find useful in the morning to increase endurance, working short-term memory, the ability to concentrate and to focus attention. However, caffeine can also cause adverse effects like high blood pressure, anxiety and sleep deprivation, especially in people with caffeine sensitivity. The impact varies by person, but many of us find that it’s best to lay off caffeine in the afternoon if we want a good night’s sleep. There are two popular options for a soothing afternoon cuppa: caffeine-free or decaf.

What is caffeine-free tea?

True caffeine-free tea is only found in the realm of herbal “teas” (more accurately, tisanes) which are made from different plants that never contained caffeine in the first place. The flavours are quite different from conventional teas, with consumer favourites including chamomile, lemongrass & ginger, peppermint, rooibos, and plenty more.

Herbal teas may be particularly attractive to those with caffeine sensitivity, which can cause anything from uncomfortable jitteriness to serious anaphylactic shock. Decaf tea may not be suitable for those with an intolerance or allergy, so it’s safer to stick with completely caffeine-free options. But if you’re not sensitive and want the classic tea experience, decaf tea may be the way to go.

How decaf is decaf tea?

The desire for an afternoon cuppa that won’t risk your sleep has motivated the development of an entire industry of decaffeinated (decaf) products. Decaf tea is made of the same Camellia sinensis leaves as a normal cuppa, but they are processed to remove the caffeine. Although you might assume from the name that decaf tea is entirely devoid of caffeine, it can actually contain up to 2.5% of the original caffeine content. This is low enough for most people, and newer decaffeination technologies mean you can enjoy the full flavour of your favourite Earl Grey without the caffeine jolt.

How is decaf tea made?

So, what are the decaffeination methods used by industry to make your decaf tea? Today in the UK, there are three main processes used: two solvent processes using dichloromethane or ethyl acetate, and an alternative extraction method that utilises supercritical carbon dioxide.

What is solvent decaffeination?

A solvent has the ability to dissolve other molecules called solutes. Think of taking a glass of water (the solvent) and mixing a teaspoon of sugar (the solute) until it dissolves. In essence, this is the same process used for solvent decaffeination, but with organic solvents (largely carbon-based chemicals) instead of water, and the compounds in tea leaves instead of sugar. To learn more about how solvents work, you can read our post about green solvents here.

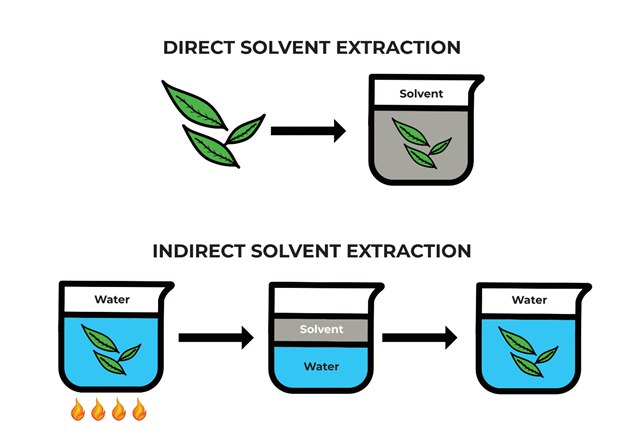

In all processes, the tea leaves are first steamed and soaked in water to increase moisture content and open the pores of leaves, allowing the solvent to penetrate more easily. Then the tea leaves can either be directly or indirectly decaffeinated.

In direct solvent decaffeination, the caffeine is removed by soaking tea leaves in dichloromethane or ethyl acetate. Most of the caffeine is extracted from the leaves into the solvent because caffeine is about 10 times more soluble in these solvents than in water at room temperature. The other major components of tea (catechins and theanine) remain in the leaves because they aren’t as soluble, which means most of the flavour stays put – in chemistry terms, the solvents are selective for caffeine. The solvent is removed, taking the caffeine with it, and the leaves are then dried to obtain decaffeinated tea. The solvent is evaporated and purified for reuse, leaving a caffeine-rich sludge to be refined and then usually sold to the beverage or pharmaceutical industry (around 25% of caffeine goes here, mostly to enhance the painkilling effect of pharmaceuticals).

With indirect solvent decaffeination, the tea leaves never touch the organic solvent directly. This method employs a current of hot water to remove caffeine from the plant, but the flavour compounds are removed as well because water is a less selective solvent. The caffeinated water is then mixed with organic solvent, drawing caffeine selectively into the solvent while leaving the other compounds behind. The water is separated from the caffeine-rich solvent and mixed with the tea leaves so they can re-absorb the flavours and oils.

Solvent decaffeination is an advantageous method because it selectively removes caffeine whilst leaving most flavour compounds behind. The process requires relatively low investment and operating costs and is easy to scale for industrial application because the equipment used is fairly standard. However, there are hazards associated with solvents that can be especially problematic for workers, and they are typically made from fossil fuels, which reduces sustainability. Furthermore, the selectivity of the solvents is never perfect – there is always some loss of flavour and aroma.

Let’s look more specifically at the different solvents used for decaffeination, and their pros and cons.

Dichloromethane (DCM, or methylene chloride)

This solvent is the most traditional one and is used by most well-known tea brands in the UK, including Yorkshire Tea and PG Tips, because it’s cheap, highly effective, and leaves no odour behind. While DCM is a hazardous solvent, using it in decaffeination is considered safe because the solvent is very quick to evaporate, meaning the trace amount left behind in the leaves is not enough to impact consumer health.

DCM has caused worker deaths in other applications (like paint stripping) due to high levels of exposure, and is suspected to cause cancer, fuelling controversy around its usage in decaffeination. While the concern for consumers is minimal, it’s important to remember that using a hazardous solvent means workers in the manufacturing plant will be exposed to it at some level, and the risk of industrial accidents is increased. It’s also a non-renewable solvent, meaning it’s not great for the environment.

Ethyl Acetate

Ethyl acetate is a newer option for solvent decaffeination, and is used in the UK by brands like Twinings and Thompsons. It is found naturally in many fruits, and even in tea itself, so you’ll frequently see decaf tea made with this solvent labelled as “naturally decaffeinated” – though the solvent itself is usually made from fossil fuels, so it’s a bit of a misleading label. Ethyl acetate is less selective for caffeine than DCM is, so the tea leaves lose more flavour, as well as picking up a bit of a fruity aroma from the solvent. However, it is relatively inexpensive, safer than DCM, and theoretically could be made renewably, so in the US most decaffeination of tea is done using this solvent. Unlike DCM, ethyl acetate is highly flammable, which means careful handling and therefore increased production costs, but aside from the fire risk there is little to be concerned about.

Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (scCO2) Method

Carbon dioxide is a cutting-edge decaffeination solvent. Its use is rare in industry, but some brands like Clipper and Brew Tea Co have adopted it. CO2 is usually a gas, but can also exist as a liquid, solid, or – under immense pressure and high temperature – something called a supercritical fluid. This is a highly compressed fluid that has some properties of liquid and some of gas. In the supercritical state, CO2 can have superior selectivity compared to organic solvents, and the selectivity can be fine-tuned for specific compounds by changing factors like the cosolvent used, pressure, and temperature. Supercritical CO2 (scCO2) is non-flammable, physiologically harmless, and abundant, making it a green solvent. However, the equipment and expertise needed for this method are different from traditional solvent decaffeination, making it expensive to adopt.

In scCO2 decaffeination, the tea leaves are usually first ground into fine particles and soaked in a co-solvent like ethanol or water. The leaves are placed in a pressurised vessel, and liquid CO2 is heated and pumped in to achieve supercritical conditions. Once the extraction of caffeine is complete, the scCO2 is removed, leaving decaffeinated leaves behind. These are depressurised, resulting in rapid evaporation of any remaining CO2 and co-solvent. It’s then removed to be dried. High-purity caffeine is recovered from the CO2 for reuse.

The process is fast, leaves no toxic residue, and is considered the best for conserving tea’s original flavour. However, it still degrades the flavour and can reduce acceptability for choosy consumers. It is expensive to set up and expensive to run because of the energy cost associated with compressing CO2 to a supercritical level, which can also impact the environmental footprint of the process.

Future developments of this method include using biofuels and optimising the selective removal of caffeine, fine-tuning the conditions so flavour compounds aren’t removed alongside it.

Water Processing Decaffeination

When compared to organic solvents, water is safer, cheaper, and more environmentally friendly – so why not use it for decaffeination? For coffee, this is actually an option known as the Swiss Water process. However, there have been a number of issues adapting the process for use with tea. The leaves are too delicate to endure being soaked in water for hours and too many of the flavour compounds are removed. This results in a tea lacking flavour and theanine (a tasty and highly beneficial amino acid uniquely found in tea). Therefore, this method is rarely used, although efforts are currently underway to make it a more viable option.

Although each method has its advantages and disadvantages. It is certainly worth splashing out for tea prepared using the scCO2 method. The higher price seems to be a small concession for better worker conditions and ultimately a greener and purer product. Loose leaf tea is also recommended to reduce the waste associated with disposable teabags.

If you’d like more information on greener replacements contact us, we can guide you.